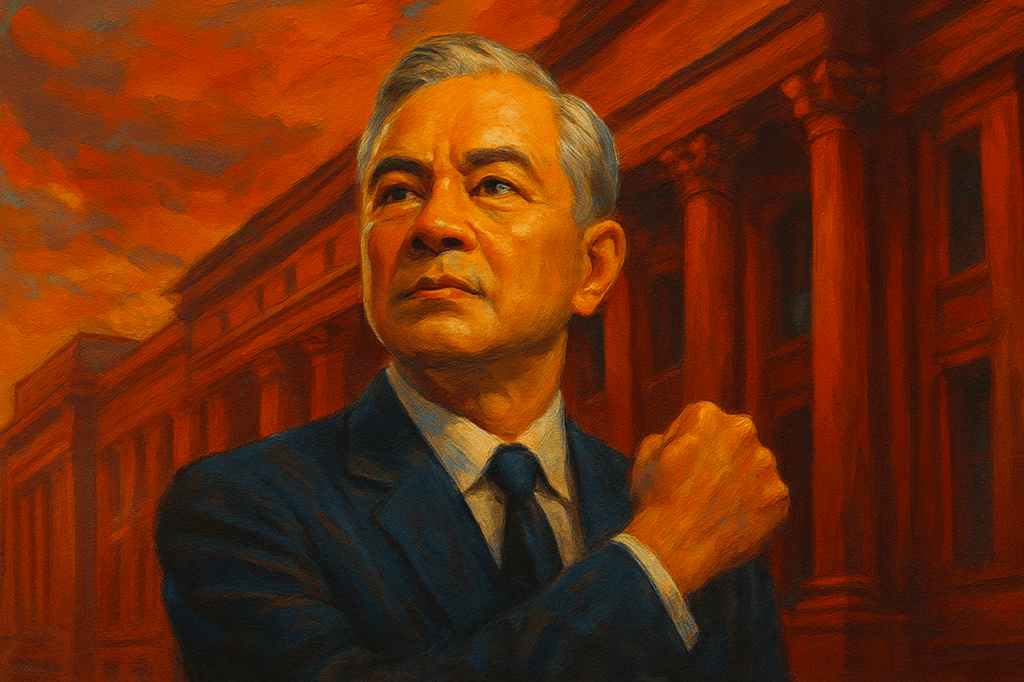

I want to start this blog with an encouragement to the Filipino moviegoers to go and watch Tarog’s Quezon if only to support the Philippine Movie industry. Technically, the movie is one of the best artistic expressions on film that had been produced recently and the actors do not disappoint.

But I would also like to encourage you to do your own fact-checking of the details included in the movie so you can have a more objective perspective on Manuel L. Quezon’s life and legacy.

The Legacy of Quezon

I know that people mostly watch movies for entertainment, but Quezon’s legacy is so much more than just entertainment. This is an important part of our history, as an independent republic and as a people, and the pride and history of a family – Quezon’s living descendants.

If you’re bringing your children to see this movie, it’s an opportunity to teach them to be critical of the information that they are being fed.

Many of the events in the movie can be verified online and I can tell you now that you will find that many of things shown in the movie really did happen, however, they’re presented through the lens of one person – the director, through the character, Joven Hernando.

Perception is everything

There were two details in the movie that felt intentionally placed — as if to nudge the viewer to think for themselves and dig deeper into the real story.

One was of Eduardo Rusca urging Joven Hernando, to see the other side of the campaign. Hernando was a staunch Quezon supporter until he supposedly witnessed what Quezon’s mudslinging had cost Emilio Aguinaldo, who was running against him in the presidential election.

Rusca was persistent, eventually convincing his nephew to go and visit the other party and observe how Aguinaldo’s ruse had affected the perception of the people on the wartime hero.

The other was when Quezon uttered the statement, something in the lines of “perception is everything,” and went on to devise a scheme to destroy Aguinaldo’s reputation with the accusation that he killed his general, the other war hero, Antonio Luna.

These two lines lingered with me as I walked out of the cinema, helping me process what I just watched. I wonder if Tarog exhibited more courage than we think.

That if my notions are true, Tarog trusted that the Filipino moviegoers would be intelligent enough to sort through the movie elements’ fact and fiction, after all, the film begins with a disclaimer that the production took creative liberties in the creation of the film.

And after the viral video on the outburst of Quezon’s grandson, Ricky Avencena, I think we need to take into consideration that the movie was intended to be satirical more than historical.

Perhaps…and just perhaps… he also intended to encourage us to engage in dialogues as we re-examine the film’s claims against what we know of our history and our state of politics.

Textbook Quezon

For most of us in our generation, we know Manuel L. Quezon as the President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines and as the “Father of Philippine Independence,” from our text books.

I’m sure we’ve touched on the Jones Law and the Tydings–McDuffie Act back in school but for most of us, our memory of these information only served us well until the final exams and only students like my late brother Nelson, who genuinely loved Philippine history, managed to remember them well into adulthood.

UP Museum of Ideas

Coincidentally, I learned more about Quezon and some of his advocacies during a visit to the UP Museum of Ideas a few months ago. One of the things that really stuck with me was this: while it was the Americans who established the Philippine General Hospital (PGH), for a time, only American doctors sat on its board of directors and performed surgeries. It was Manuel L. Quezon who pushed for and advocated that Filipino medical practitioners be allowed to train and practice alongside their American counterparts which eventually led to Filipino doctors gaining seats on the hospital’s board.

I can’t say that Quezon was without flaws, whether in his personal life or in his politics, but his accomplishments reflect a deep conviction that Filipinos deserve the freedom to govern their own land as they see fit.

Hare-Hawes Cutting Act vs Tydings-McDuffie Act

Since I’m on this topic, let me point out that in the movie, Joven Hernando (remember, he’s a fictional character) narrates that Quezon went to the United States to renegotiate with the Americans and came home with the Tydings–McDuffie Act, which overrode the Hare–Hawes Cutting Act previously negotiated by then Vice President Sergio Osmeña and Senate President Manuel Roxas.

According to Tarog’s Quezon, Quezon was displeased that Osmeña was receiving most of the credit for securing the Philippines’ independence from American rule.

When I looked it up, it turned out to be true that Quezon did travel to the U.S. to renegotiate, but what’s even more important is understanding the difference between the two acts. While they may seem similar, they are not.

Under the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act, the Americans could decide on their own whether to keep military bases in the Philippines. In contrast, the Tydings–McDuffie Act stated that the U.S. could maintain bases only with the Philippine government’s consent.

See the difference?

It’s a small but crucial detail, and for me, it’s very consistent with everything Quezon stood for – his belief that Filipinos should have a say in their own affairs, regardless of whatever personal ambition he might have had.

To me, the accusations that he re-negotiated because he wasn’t getting the credit is so…gossipy. So crab-like.

One of the things I noticed about us, Filipinos, is that we are too sensitive sometimes. We like things sugarcoated and cushioned, that when one’s personality is abrasive and assertive, we often see it as arrogance and easily take offense.

Again, I’m not saying that Quezon is a saint. All I’m saying is that perhaps some of these accusations are rooted to our cultural tendencies more than Quezon himself. I’m sure Quezon made a lot of mistakes, but the the Tydings-McDuffie act was not one of them.

Dirty Politics

I say “some” because some of the accusations in the movie are true. For instance, it was true that during their respective campaigns, Quezon and Aguinaldo both played dirty. Quezon insinuated that Aguinaldo had General Luna and Gat Andres Bonifacio killed – and according to hearsays, to the extent of exhuming the remains of Bonifacio and displaying it for public.

It must be noted that there are no definitive evidence that Aguinaldo had a part in killing Luna and Bonifacio. These claims are merely speculations and interpretations largely based on “testimonies.”

What was true was that Luna was executed by Aguinaldo’s men under his authority, but his direct involvement to this has yet to be proven.

Aguinaldo also used Quezon’s previous relationship with a provincial lass to up his campaign, but I guess Quezon’s scheme was far darker in comparison. If anything, it just shows how, even back then, we Filipinos were more inclined to believe the worst about a person more than the good. Quezon knew it and used it as a tool to win.

It was also true that while Quezon and Osmeña strongly opposed then appointed Governor General Leonard Wood’s policies, Aguinaldo, who swore allegiance to the United States to end the war, agreed with Wood that the Philippines was not ready for autonomy. Aguinaldo believed that working with the Americans and aligning with their governance was the best path for the Filipino people.

I don’t know if it’s true that Quezon sought Aguinaldo’s help in speaking against Wood as was shown in the movie, but historical records does state that the latter supported the US initiatives in the Philippines.

By the way, that scene when Quezon declared Aguinaldo as a war hero happened after he was elected President.

The film

I thought Jericho Rosales was brilliant in this movie. I immediately shifted from seeing him as the actor to him being Quezon. He was charming, intelligent, arrogant, and dripping with charisma.

Romnick Sarmienta’s portrayal of Sergio Osmeña was the perfect complement to Jericho Rosales’s Quezon. Sarmienta has surely come a long way from his teen idol days. Rosales’ charm and wit wouldn’t have landed as perfectly had they casted the wrong Osmeña.

And did you catch his Cebuano accent?

I also thought that Mon Confiado was able to play Aguinaldo with the dignity of a war hero.

Other notable performances are that of Joross Gamboa, Aaron Villaflor, Bodjie Pascua, Karylle Tatlonghari and JC Santos.

The period sets and costumes were beautiful. I actually think Quezon had better locations and visual textures than Heneral Luna and Goyo.

Speaking of Goyo, I can’t help but suspect that one of the production’s goals was to challenge the way we see our heroes. In that movie, Goyo also seemed like the unlikely hero. Just saying.

Quezon is undeniably a well-made film, but if I may say so, a tad too long for a movie centered on dialogues and narrations.

Are the Filipinos ready for this type of storytelling?

What came to mind while reading up on the controversies surrounding Tarog’s Quezon was The Greatest Showman, a movie musical inspired by the life of P.T. Barnum. That film also took great liberties in fictionalizing the story for entertainment.

To me, Quezon felt like I was watching a movie about something else. It’s like it’s him but it’s not really about him. It felt more like a call to re-examine today’s politics and governance.

And in some ways, I felt that I was being dictated on how and what to think, which I do not like. Give me the data and let me draw my own conclusions.

It isn’t a documentary, as one review points out, but are the Filipino audiences ready for this kind of storytelling?

I can understand why Quezon’s descendants feel indignant about the film. There are no clear lines separating what’s historically accurate from what’s dramatized and we all know that generally, Filipino viewers tend to take historical films at face value.

Perhaps Tarog may have been bold to trust that audiences would do their homework, but that’s a huge risk when so few actually will.

Here’s a great commentary from Mighty Magulang:

References you can read through:

Hare-Hawes Cutting Act

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hare-Hawes-Cutting-Act

The Philippines, 1898–1946

https://history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/APA/Historical-Essays/Exclusion-and-Empire/The-Philippines/

THE PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENCE ACT (TYDINGS–MCDUFFIE ACT) 1934

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tydings-McDuffie-Act

Immigration History summary of the Act

https://immigrationhistory.org/item/tydings-mcduffie-act/

The Quezon-Osmeña Split of 1922 – The Ateneo Archium

https://archium.ateneo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4925&context=phstudies

Pictures, timelines, and readings by Manuel L. Quezon https://mlq3.substack.com/p/pictures-timelines-and-readings

Memorandum by the Chief of the Division of Philippine Affairs – Section 2(12) of the Tydings-McDuffie Act

https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945v06/d887

Leave a Reply to gentlebim Cancel reply